IOS lecture on Affordable Access to Quality Higher Education and Muslim Minorities

IOS lecture on Affordable Access to Quality Higher Education and Muslim Minorities

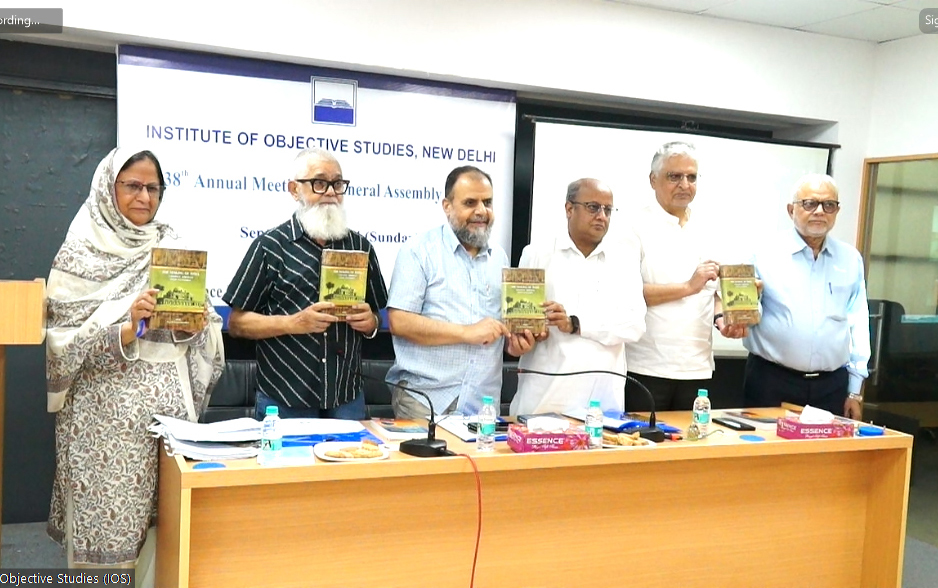

New Delhi: The 38th annual meeting of the General Assembly (GA) of the Institute of Objective Studies concluded on September 8, 2024. On this occasion, a lecture program on ‘Affordable Access to Quality Higher Education and Muslim Minorities’ was organised by the Institute at its auditorium.

The lecture was delivered by Prof. Furqan Qamar, professor of management, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Introducing the speaker, the vice chairperson of the IOS, Prof. (Ms.) Haseena Hashia, said Prof. Qamar is a former vice-chancellor of the Rajasthan University and the Central University of Himachal Pradesh. He is also ex-secretary general of the Association of Indian Universities. He is a well-known academician and his contribution in the field has been recognized in India and abroad, she noted.

Delivering the lecture, Prof. Furqan Qamar, expressed concern over declining proportion of Muslims in education. One of the reasons for this decline was that education had become a costly affair which majority of Muslims no longer afforded. Both the government and the community leaders were worried that 15 percent population of the country was lagging behind in education, leading to the lack of employment opportunities for them. What was happening since the last 12 years was also causing concern. But, one must not get disappointed and hope that good days would return. He said that if a community wanted to progress, it must participate in politics. It was also a matter of concern that the Muslim representation in politics was declining. The Sachar Committee report in 2006 showed mirror to the plight of Muslims. The report described Muslims as the largest minority and the second largest majority in the country. Despite this, there were only 58 IAS officers in the country as against about 150 if taken into account their numerical strength. Referring to the latest edition of the All India Survey of Higher Education (AISHE) published by the Ministry of Education, Government of India, he said the number of Muslims in higher education declined from 21.10 lakh in 2019-20 to 19.22 lakh in 2020-21. Thus, 1.79 lakh Muslim students are missing from the country’s higher education system. As a result of this, the share of Muslim students in higher education decreased from 5.45 percent to 4.64 percent during the corresponding year.

Prof. Qamar held that it was for the first time that the enrolment of Muslims in higher education declined on a year-on-year basis. Until 2019-20, their numbers had been increasing though varyingly and gradually increased from 6.97 lakh (or 2.53 percent of the total enrolment in higher education) in 2010 to 21.01 lakh (5.45 percent). He noted that before 2014 and after the Sachar Committee report, the enrolment of the Muslim students in higher education registered 11-12 percent rise. But, according to the 2021-22 report, this came down after 2014. A decline in Muslim enrolment in higher education by 8.53 percent in one year was simply inexplicable. He questioned if the pandemic caused it. But, if it was so, why only the Muslims were affected. They were not the only social group which was economically poor and socially disadvantaged. “While it may be perplexing to pinpoint the reasons and causes for the sudden drop the low enrolment of Muslims in higher education in India. It is generally attributable to a combination of socio-economic factors. Educational disparities, natural and perceived discrimination are some of the factors that contribute to the drop in their enrolment”. He further said that socio-economic conditions played a pivotal role in determining access to higher education. Most of the Muslims in India came from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and faced access barriers due to poverty and the lack of financial resources. Economic challenges also restricted their ability to pursue higher education due to rising costs of receiving education, he added.

Prof. Qamar pointed out that the real barrier was ostensibly seen after 2014 when the new government at the Centre was installed and it took oath of office to uphold the Constitution. But the question was whether it acted as per the spirit of the Constitution. Their indifference to the community was one of the reasons for Muslims’ inaccessibility to education. In this context, he referred to Assam chief minister’s diatribes against Muslims. He also took note of an analysis which said that Muslims wanted to give education to their children but financial constraints and government’s apathy prevented them. This also led them to send their wards to madrasas. A mere 2.5 to 3 percent children are enrolled in madrasas. Some of the madrasas are recognized by the Madrasa Board. He said that the ratio of girls in enrolment was higher than the boys. Girls were performing better than boys. This trend was visible across religions. Under the Right to Education Act (RTE), enrolment from class 1 to 10th was compulsory. But, till the children reached class 10th, a large number of them dropped out. Significantly, the rate of dropouts declined in 11th and 12th classes. He held that economic weakness was the main cause of drop-outs after 8th class. They did not send their children to Industrial Training Institutes (ITI) either and engaged them in other occupations. He said that out of 21 lakh, 5 lakh Muslims took admission in various institutions.

Prof. Qamar maintained that the other reason for the higher rate of drop-outs was non-implementation of the Sachar Committee report which recommended that Muslim students should also be awarded scholarships. Scholarships being given to Muslim students had since been discontinued. The number of Muslim students studying in various institutions stood at 5 lakh. While 3.4 percent students were studying in central universities, 90 percent and 10 percent Muslim students were receiving education in colleges and other universities respectively. Fifty to sixty percent colleges had vocational courses. He said, “They do not get education in the institutions from where they could progress. Institutions where they study cannot ensure a job to them”. Muslims opened a number of schools. In UP, there is a chain of Islamia colleges. There were a number of schools from where the functionaries entered politics. More often than not principal and the manager in Islamia Colleges are at the loggerheads with each other. In order to make them more viable, quality of education should be improved. Besides, facilities for teacher’s training and technical support should be put in place. He urged the community leaders to convince the community that they had equal rights before the eye of the law.

Prof. Qamar opined that there were two goods – merit good and public good. While the activity like planting trees comes under merit good, benefiting himself and others, falls under the category of public good. Education also comes under this category because, besides benefiting oneself, it benefits society. A substantial amount of money should be spent on education. According to the recommendations of the Kothari Commission, 6 percent of the GDP should be spent on education. Out of this, 2 percent each should be spent on primary and secondary education. Today, instead of being public good, education had become a public responsibility. This was why education entered the domain of private sector. About 90 percent medical colleges and70 percent technical institutions were in the private sector. Private institutions were subsisting on the fees from students. Some philanthropists made donations to certain private institutions like Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi. Today, higher education is beyond the reach of the common man. Referring to the universities in the private sector, he said that private universities were replacing government-run universities. They were subsisting on loan and heavy fees, instead of government grant. Universities like Aligarh Muslim University, Jamia Millia Islamia and Delhi University charge less frees from the students but due to the lack of hostel facilities, they are forced to take private accommodation in the town, he noted.

Prof. Qamar pointed out that education today was very costly and most of the parents were unable to afford it. There is mushrooming of coaching institutes for preparing candidates for admission to IITs and medical colleges. These coaching institutes charge exorbitantly from the candidates. Since quality education is very costly, it poses a big challenge before the parents, he said. Members of Scheduled Castes and Schedule Tribes did benefit from reservation, but for Muslims it remained elusive. Laying stress on the need for good schools, he urged the management of Islamia colleges to end politics and raise the standard of teaching. There were about one lakh seats in medical colleges and an amount ranging between Rs. 1 crore and Rs. 4 crore was being charged by the private medical college as fees. This leads the candidates to seek admission to medical colleges in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, etc.; where fee structure was cheaper compared to India. While calling for the identification of the problems and their resolution, he felt the reasons were either structural or financial.

Prof. Qamar commented, “Muslims in India suffer on account of the misconception of being outsider, invader, anti-national, pro-Pakistan, descendants or cruel rulers who committed atrocities on Hindu natives of India. Sadly, NEP 2020 hardly does anything to break this stereotype. It may be hoped that the just constituted steering committee for the national curriculum framework would address”. He further said that what the community needed was handholding and support to make it to the mainstream higher education in a much larger numbers commensurate with their share in the population. Silence on or sidelining these issues on the part of the policy, did not go with ‘Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas and Sabka Prayas’. The majoritarian overtone in the policy might not only alienate its own nationals from contributing their might to national development, he concluded.

In his presidential remarks, the Chairman of the IOS, Prof. M. Afzal Wani observed that Prof. Furqan Qamar’s lecture provided hints that could be helpful in solving problems. They could also serve the vision document for Muslims. He said that the IOS would give it wide publicity for the benefit of Muslim educational institutions. His speech ignited a new spirit in the community. He urged Muslims to take his speech to heart. He suggested to the Muslim institutions to invite Prof. Qamar for his lecture on the subject that was so vital for the benefit of the community.

Earlier to the lecture program, the following two important publications brought out by the Institute of Objective Studies were released during its General Assembly meeting:

1. The Making of India: A Journey through Eight Centuries, edited by Prof. Syed Jamaluddin

2. Inter-Religious Understanding for Universal Equality and Fraternity, edited by Prof. M. Afzal Wani.

At the end of the lecture, Vice-Chairperson of the Institute, Prof. (Ms.) Haseena Hashia proposed a vote of thanks.

A view of audience

Go Back